But the fifties were never as

simplistic as they seem to be on the surface.

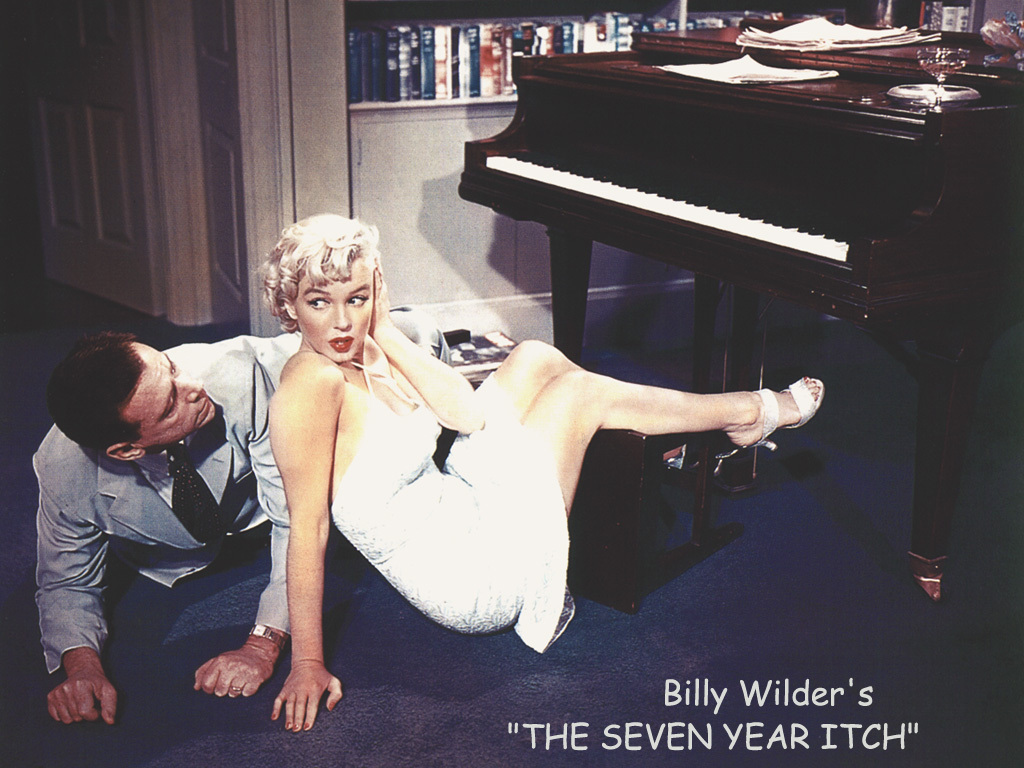

If “Seven Brides for Seven Brothers” represents a world where women are

placated with a smile and a bow, where being a housewife is the best and most

important thing a girl can be, then the world of Marilyn Monroe’s movies from

the same general period of time are in retrospect a feminist answer to such

morays. In “The Seven Year Itch”,

“Gentlemen Prefer Blondes” , “Bus Stop” and “How to Marry a Millionaire”,

Marilyn’s characters dance through the screwball motions of comedic buffoonery

on her way to snagging (or losing, or even ignoring) men, but they have

something to say: treat me with respect, or lose me forever.

Lorelei Lee, Marilyn’s “Gentlemen

Prefer Blondes” character, is seen by the men around her as a mindless cream

puff and an easy lay, which is part of the complicated reason why she’s gone

gold digging for a guy of her own. If

men aren’t about to respect her then she might as well go for the only reliable

thing in the world – cold, hard cash.

Alongside her best friend and fellow showgirl Dorothy, Lorilee

ultimately stays true to the rich guy who’s always been besotted with her,

laying firm waste to those who think her loyalties might twist in the wind for

a bigger paycheck. That’s not to say that the movie’s perfect;

her choice to stay with the big bucks is validated and never challenged, unlike

Dorothy’s passion for athletic muscle men, which is subverted when she falls

for private dick Malone. But it’s when Lorilee shows her wisdom to her

fiancé’s skeptical father it proves that she’s not just a body, not just a

showgirl, but a bright, slightly bitter, girl who happens to love a rich guy.

Pola, the girl from Marilyn’s

other 1953 offering “How to Marry A Millionaire,” has much simpler aims, and a much

simpler problem. Extremely nearsighted

in a world where contacts have not yet become the norm, Pola’s hunt for a rich

husband is complicated by her belief that men don’t find women in glasses sexy. Thus she’s completely unable to notice that

the man before her is a complete con artist, and thus she ends up on the wrong

plane going in the wrong direction the day she’s supposed to marry him – resulting

in her meeting a bespectacled guy who’s interested in her because of her

glasses. Unlike Lorilee, Pola marries a poor man, but

more importantly a man who loves her for who she is, glasses and all, and who

WANTS her to see the road before her.

Then there’s the nameless blonde

who’s the subject of the paranoid and beguiling fantasies of Tom Ewell in The

Seven Year Itch. Stuck in New York

during a mind-bendingly hot summer, he is alone, his family in Maine for a vacation. Rebelling against the cigarette-free, low-fat

world of his marital confines, our

protag makes the acquaintance of a young blonde actress who soon possesses his

erotic fantasies. There’s much

conjecture as to what’s really happening in the movie’s reality and what exists

in the fantasy world of Richard

Sherman’s fantasies; is the plumber a detective or an everyday working

man? Does the single girl upstairs want

to seduce him or is he projecting his neuroses on her? What matters is that she embodies everything

tempting and sweet that his wife no longer represents to him, and only when his

wandering mind imagines that his wife’s having an affair with someone at the

resort does he snap out of his reverie and run off to Maine, Marilyn’s lipstick

on his head and his shoes sailing out of the apartment window. One of the very first sex farces in coded

American cinema, Marilyn embodies that lustful daydream that everyone seems to

harbor, most specifically every straight man – that it’s possible to charm the

seductive girl next door into an affair with you, that the blonde that’s miles

out of your league will fall in love with you.

But Monroe’s nameless character also represents the societal fear that

guileless sex will corrupt, seduce and lead astray the morally righteous – that

if you leave a man alone for too long he’ll fall victim to his basic instincts. The girl herself meanwhile has no say in the

fantasy, absolutely nothing to do with it – her actual thoughts and feelings

about things that don’t involve him are about as important to Sherman as his

son’s need for his kayak paddle, which his wife has asked him to forward to the

family. The Girl exists to ooze

sexuality – seriously, most everything she says to him somehow relates to her

sleeping in the nude, taking nude pictures, being so hot she had to take a bath

– nudey nudely nudity. She also exists to

be overwhelmed by his kindness, to let her skirt blow in the air and let

America at large play voyeur in one of the most famous moments in cinematic

history, and to be innocently impressed.

In a bizarre way it’s a light-hearted version of Lolita where the blonde

girl whose life, opinions and wit, even her name, are circumvented by the unreliable male

narrator; yet even Sherman’s unreliable narration can’t stand up to the morays

of the 50s. That Good Ol’ American Institute stays intact, and the Girl gets to

sleep in air-conditioned peace for the next few months.

Bus Stop is rather different – for

Marilyn’s character, Cherie, an untalented saloon singer with a past, is

running away from marriage to awkward cowhand who’s determined to have and keep

her – and drag her home to an isolated ranch.

She struggles with the shame inherent in her business, the cowhand’s

lack of respect for her opinion and desires…and a snowstorm that traps her with

him at the titular bus stop. Ultimately,

Beau has to figure out that to win Cherie’s hand, he’ll have to open his ears

and actually pay attention to her. Much

like Lorellie and Pola before her, Cherie learns that without respect all the

lust in the world means nothing – and it’s something Bo learns before it’s too

late, shedding his childhood like the snow at the bus stop and taking Cherie’s

hand with pride.

No comments:

Post a Comment